Who won the ICC withdrawal case?

In Pangilinan v. Cayetano (March 16, 2021), the petitioners asked the Supreme Court “to: (a) declare the Philippines’ withdrawal from the (International Criminal Court or ICC) as invalid or ineffective, since it was done without the concurrence of at least two-thirds of all the Senate’s members; and (b) compel the executive branch to notify the United Nations Secretary-General that it is cancelling, revoking, and withdrawing the Instrument of Withdrawal” for being “inconsistent with the Constitution.” When the decision came out, both the petitioners and the respondents claimed victory. Why?

The petitioner-senators led by Sen. Francis Pangilinan claimed success because prior to the issuance of its decision, the Supreme Court handed out a press release, dated March 16, stating “…that the President, as the primary architect of foreign policy, is subject to the Constitution and existing statute…”

Later on, after the text of the unanimous, 101-page decision was released by the Court on July 21, the Senate issued its own press release, dated July 22, saying: “We welcome the guideline pronounced by the Court that ‘even if [the Philippines] has deposited the instrument of withdrawal, it shall not be discharged from any criminal proceedings. Whatever process was already initiated before the (ICC) obliges the state party to cooperate.’ [p.87] We take this as a step in the right direction towards attaining government accountability and substantial justice.”

Simply stated, the senators were gladdened by the Court’s statement that though the Philippines had withdrawn from the ICC, President Duterte and his subalterns could still be ensnared by the ICC for crimes committed prior to the Philippine withdrawal.

They probably related this statement to former ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda’s much-publicized finding that “the crime against humanity of murder has been committed… in the Philippines between 1 July 2016 and 16 March 2019 [date of the Philippine withdrawal] in the context of the war on drugs” and even “… as early as 1 November 2011.” (For details, see my June 27 piece, “Demystifying the ICC prosecutor’s bravado.”)

The respondents, mainly Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea and Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr., also claimed victory because the Court dismissed the petitions for being moot and did not order them to notify the UN secretary-general that our country was “cancelling, revoking, and withdrawing the Instrument of Withdrawal.”

Presidential spokesperson Harry Roque explained that the Court’s extended discussions, especially the “guideline” that delighted the senators, were mere obiter dicta or side comments that cannot be considered jurisprudence or case law. Consequently, the President is not obliged to cooperate with the ICC in any inquiry into the government’s drug war.

Given these conflicting claims, who really won? In Velarde v. Social Justice Party (April 28, 2004), a unanimous Court en banc held that the dispositive portion of a decision determines who or which side won. Plainly then, the respondents won because, to repeat, the petitions were “DISMISSED for being moot” (all caps and bold types in original). Only the portions supporting this disposition constitute the ratio decidendi (rationale for the decision) and are binding. All other statements are not binding and cannot be cited as precedents.

In a recent forum, the legal eagles in the University of the Philippines critiqued the Court for talking too much. Its resident constitutionalist, retired justice Vicente V. Mendoza, grumbled, “Was there a decision? Is Pangilinan v. Cayetano a decision? To me, it is not a decision; it is a mere advisory opinion” barred by the Court’s Internal Rules.

Nonetheless, in my humble view, the decision — penned by the erudite Justice Marvic M.V.F. Leonen, a UP alumnus and former law dean — was probably signaling that if a new, live (not moot), and proper petition is filed, the current members of the Court who all signed the decision without any reservations or separate opinions will uphold their obiter.

It faulted the petitioners for their failure to file their pleas on time. They should have filed them before the withdrawal of the Philippine membership in the ICC became a fait accompli, that is, before the ICC accepted the said withdrawal. However, the Court did not bar the filing of new petitions in which the substantive issues in this case are raised in ways that “conform to the basic requisites of justiciability.” (p.100)

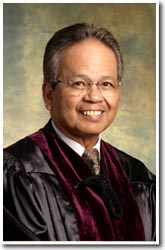

By: Former Chief Justice Artemio V. Panganiban

Comments to chiefjusticepanganiban@hotmail.com